As the race for the 2020 U.S. presidential election heats up, so too does the race to secure the voting infrastructure. As part of #Protect2020, state and local governments, election officials, federal partners, and vendors have made an effort to increase collaboration “to manage risks to the nation’s election infrastructure.” In September, the Senate Appropriations Committee approved a $250 million bill to help states improve election security.

These large initiatives show a collective effort to “do better,” but what does that mean on a day-to-day, tactical level?

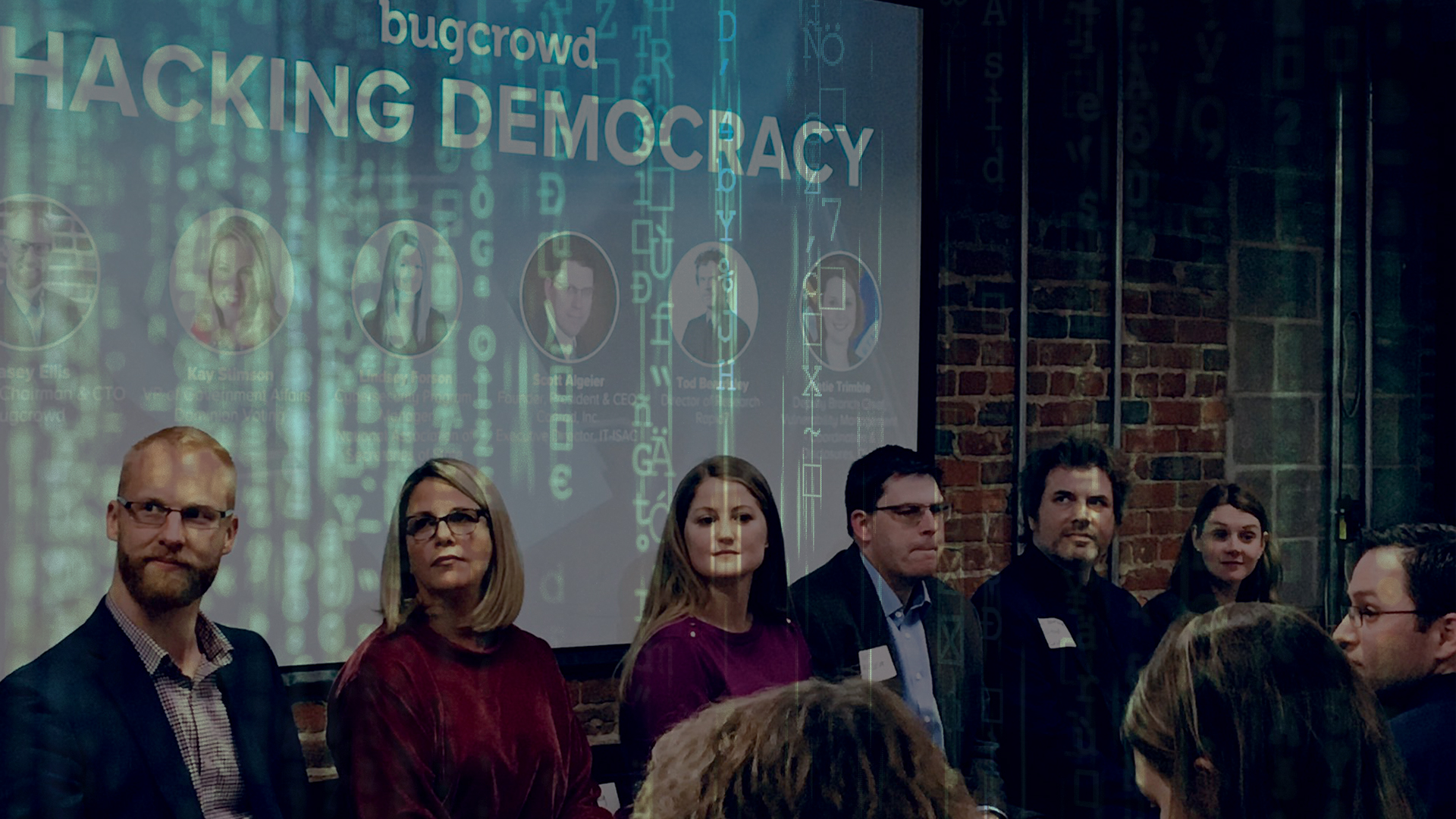

Last Thursday, the team at Bugcrowd hosted “Hacking Democracy,” a panel and networking event that provided an open forum to discuss what’s being done to protect the American voting process. Casey Ellis, Chairman, Founder and CTO at Bugcrowd, sat down with the following local industry experts to discuss election security:

- Scott Algeier, President and CEO of Conrad. Inc. and Executive Director at IT-ISAC

- Tod Beardsley, Director of Research at Rapid7

- Lindsey Forson, Cybersecurity Program Manager for the National Association of Secretaries of State

- Kay Stimson, VP of Government Affairs at Dominion Voting

- Katie Trimble, Deputy Branch Chief, Vulnerability Management – Coordination and Disclosures (VM C&D) Branch of CISA, Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

The conversation around election security is essential and the panelists provided insight into the challenges and achievements that have taken place over the past three years. There were several takeaways from the evening’s discussion:

1. Voting machines are just the beginning of the story

Last week, a John Oliver video on voting machines went viral. The segment was funny and shed some light on issues that are being addressed, however it illustrated a point that the Hacking Democracy panelists all agreed on – a disproportionate amount of public conversation focuses on voting machine security. They emphasized that non-technical voters should be informed about the scope of solutions.

Over the past three years, the government and private sector have teamed up to make plans, provide resources and create communications protocols for how information should be shared. Additionally, federal and state officials established the Elections Infrastructure Information Sharing and Analysis Center™ (EI-ISAC®), creating a formalized collective to help secure the U.S. elections infrastructure.

Efforts have also been made to modernize databases, replace machines, hire staff, conduct risk assessments, allocate resources, establish multi-factor authentication and prepare for incident response. However, some state legislatures require a voter-verifiable paper record in case electronic systems are called into question.

Panelist Lindsey Forson emphasized there is an overwhelming trend to move toward paper-based systems. For example, South Carolina recently announced a transition to a paper-based voting system. Residents are expected to cast their votes using the new system starting with the presidential primary in February 2020. “Voters will make their selections on a touchscreen. Paper ballots will be printed off, and voters will then feed the paper ballot into a scanner that counts and records the votes.” According to the South Carolina Election Commission, this is intended to provide a paper trail for votes, which will be saved for auditing and verification.

The consensus for securing the election infrastructure is that there are many answers, not a single one. A lot of work is being done to make these solutions compatible.

2. Coordinated vulnerability disclosure programs are making a difference

While replacing legacy systems has been the focus for 2020, there’s also been a concentrated effort to improve updating and patching processes. This would not be possible without coordinated vulnerability disclosure. The DHS is working with EI-ISAC and Secretaries of State to proactively invite researchers to “say something, if they see something.”

Engaging coordinated vulnerability disclosure — where researchers report a vulnerability to DHS — helps to efficiently mitigate the issue and disclose a patch. From the vendor side, Rapid7’s Tod Beardsley said, “The significance of adopting normal coordinated vulnerability disclosure is wildly different than it was four years ago.”

3. VOTE!

American citizens generally trust the voting process – they register, show-up and complain. No one should be frightened or discouraged from voting. As Beardsley said, collectively showing up to vote is like joining the neighborhood watch for the internet. Voter turnout dilutes the attackers’ ability to sway elections.

It’s also important to remember that elections happen all the time – not just every four years. Local level elections (mayors, town councils, etc.) are just as important as national elections.

Quoting Pennsylvania Secretary of State, Forson said, “Election security is a race without a finish line – it’s the most demanding IT problem in the government right now.” It is an ongoing challenge in an ever-evolving environment with limited resources. The good news? Since 2016, federal organizations and the private sector have teamed up significantly to collaborate to improve the U.S. election infrastructure — and their work will continue until elections are fully protected from outside interference.